“

The Indus Valley Civilization, one of the world's earliest urban cultures, left behind a legacy rich in archaeological and historical significance. In this article, we explore 20 fascinating facts about burial practices and mortuary customs, revealing how the people of the Indus Valley approached death, the afterlife, and the rituals that accompanied their burial practices.1

1

”

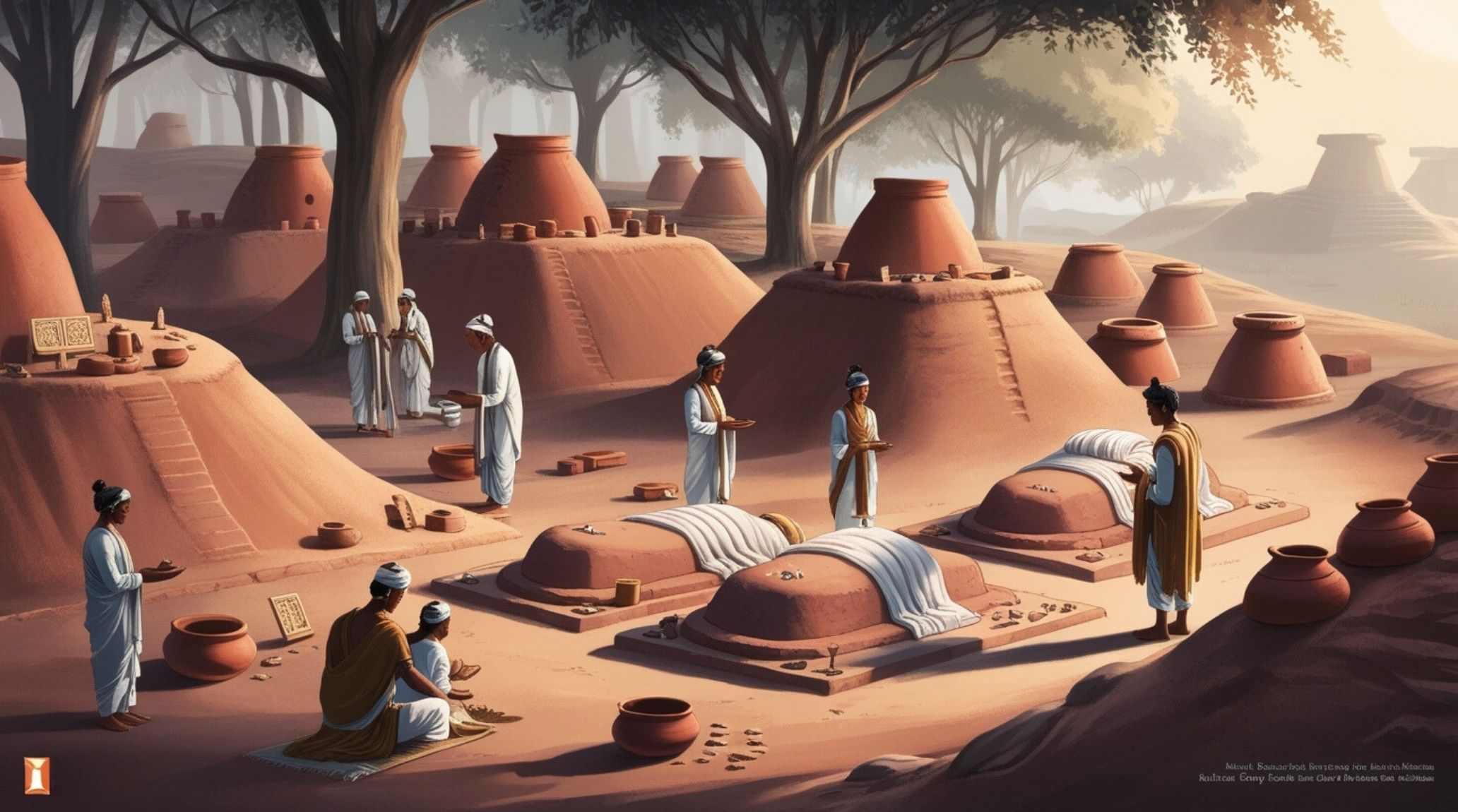

At Harappan excavation sites, over two hundred bodies have been uncovered. Burials were mostly in large, mud-brick-lined pits, occasionally oval or rectangular. Some graves contained wooden coffins, with only stains remaining as evidence.1

In the Indus Valley Civilization, burial practices varied widely, with some individuals interred in formal cemeteries and others found in more informal or isolated settings. This suggests a complex relationship between social status and burial practices.2

Burials in the Indus Valley were conducted using several methods, including inhumation (burial of the body) and cremation. Inhumation was the more common practice, with bodies placed in pits or wooden coffins.3

At Rakhigarh, distinctive pits were carved to create an earthen mound beneath which bodies were buried. This method resulted in unique burial features. The bodies were interred beneath these raised earth formations.4

Research at Kalibangan reveals that many pots were buried with individuals, likely for use in the afterlife. A copper mirror found with a woman suggests that the Harappans may have believed in using mirrors to interact with the spirit world.

In Lothal, some graves contained the bones of two individuals, initially interpreted as possible evidence of sati. However, this theory is challenged by findings of graves with two male individuals, suggesting other explanations.5

At Kalibangan, graves arranged in groups of eight or more were found in large, uncovered rectangular pits filled with pottery and bodies. This arrangement is likely associated with individual families.6

Some graves contained symbolic artifacts, such as seals with intricate designs, which may have represented personal or religious significance, enhancing the understanding of the individual's identity and beliefs.7

There is evidence that skulls were sometimes removed from graves and kept separately, possibly for ritualistic or ancestral purposes. This practice reflects a complex relationship between the living and the dead.8

Infants and children were buried with care, often accompanied by toys or small objects. This indicates a special treatment for younger individuals and the importance of their role in the family or community.9

Stray finds at Rojdi included the bones of two infants buried beneath a house floor. At Mohenjo-Daro, known as the mound of the dead, baskets of bones and a single skull were discovered in various houses.10

At Sukotda, numerous animal remains, primarily cattle like sheep, goats, horses, and dogs, were discovered. Dholavira, one of the largest found cities, also had animal bones, along with a significant number of weapons and ornaments.11

Excavations around Harappa revealed over 100 pot burials, typically designed to contain only a single set of bones. However, there were exceptions, such as pots with three skulls or mixed bones of multiple individuals.12

In the burials, the skull was centrally placed, with long bones arranged slantingly and smaller bones filling any remaining spaces. These pot burials were found very close to the land surface.13

In some cases, wooden coffins or structures were used to encase the body, reflecting an effort to protect or honor the deceased in a more elaborate manner.14

There were regional differences in burial practices within the Indus Valley, with distinct customs observed in different cities and towns, suggesting diverse local traditions and beliefs.15

Unlike some other ancient civilizations, the Indus Valley Civilization did not produce monumental tombs or pyramids, reflecting different societal values and beliefs about death and the afterlife.16

Burial practices varied between urban centers like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro and rural areas. Urban cemeteries showed more standardized burial practices, while rural areas had more variability.17

Unlike some ancient cultures, there is no evidence of ritual sacrifice associated with Indus Valley burials, indicating different approaches to funerary rites.18

Evidence suggests that ancestors may have been venerated through specific rituals or practices, as seen in the treatment of certain graves and the presence of ancestral skulls.19