“

Understanding how the brain processes emotions reveals the deep connection between our biology and behavior. Emotions aren't just feelings—they're powerful chemical and neural responses shaped by evolution. The brain interprets, generates, and regulates emotions using complex networks, particularly involving the limbic system, prefrontal cortex, and various neurotransmitters. 1

1

”

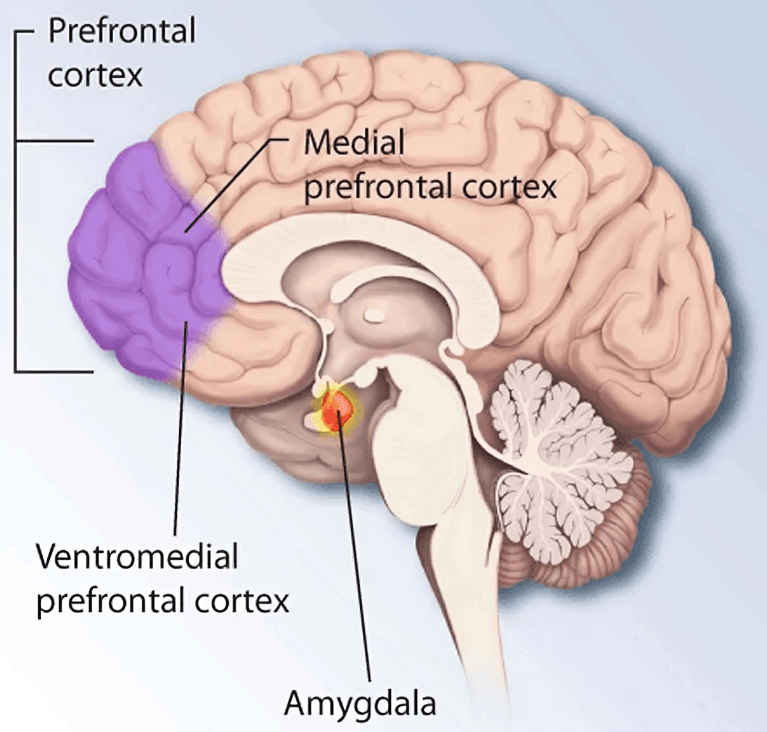

The amygdala is a key emotional processing hub that rapidly detects threats and triggers responses like fear or aggression, often before we're even consciously aware of what caused them. 1

The prefrontal cortex helps regulate emotional impulses by reasoning through them. It works to balance raw emotional reactions from the amygdala with logic, context, and long-term thinking. 2

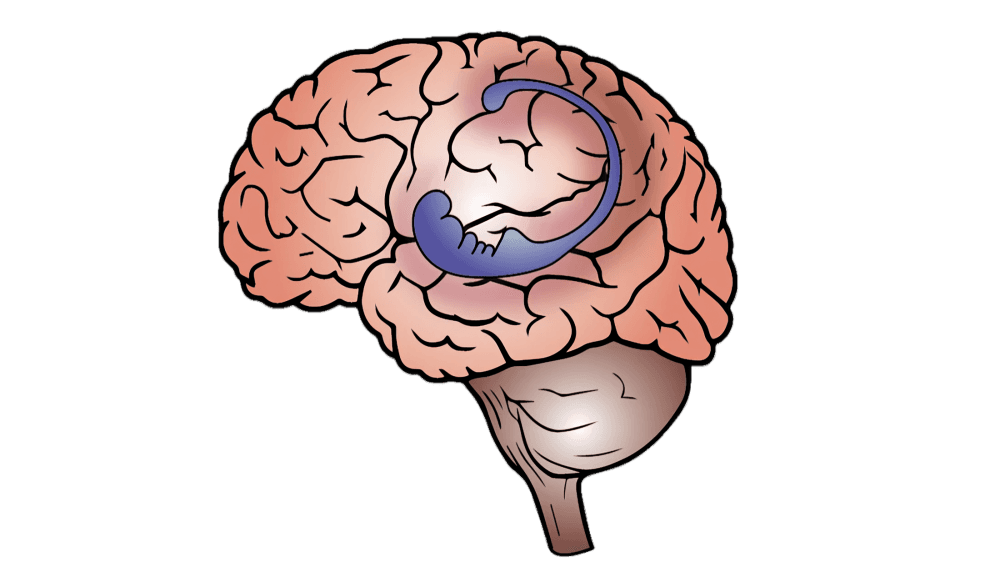

The hippocampus links memories with emotions. When you recall a specific moment, the associated feelings—joy, sadness, fear—are reactivated, helping you learn from past experiences and form emotional habits.

Neurotransmitters like dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine influence how intensely we feel emotions. For instance, low serotonin is linked to depression, while dopamine enhances feelings of reward. 3

The insula plays a role in emotional awareness, especially empathy and disgust. It helps us sense internal bodily states and interpret emotional cues in others, building social understanding. 4

Brain imaging shows that positive emotions often activate the left prefrontal cortex, while negative ones like fear or anger are associated with more activity on the brain’s right side. 5

Mirror neurons help us “catch” others' emotions. These specialized brain cells fire both when we perform an action and when we observe someone else performing it, explaining emotional contagion. 6

Oxytocin, often called the “love hormone,” is produced in the hypothalamus and fosters bonding, trust, and warmth, playing a key role in how we emotionally connect with others. 7

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) monitors emotional conflicts, helping us manage contradictions like loving and resenting someone at the same time or feeling guilt during happiness. 8

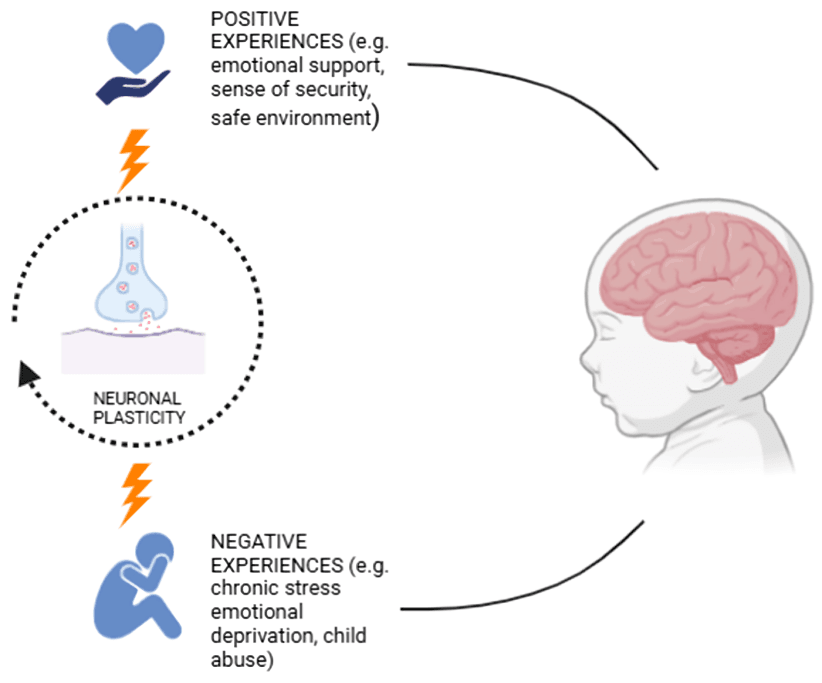

Childhood experiences deeply shape emotional processing by strengthening or weakening specific neural pathways, especially those involving safety, attachment, and resilience in the face of emotional distress.

Emotional memories tend to be stronger than neutral ones because of the amygdala’s role in enhancing encoding during emotional events, ensuring the brain pays attention to survival-relevant experiences. 9

Emotional regulation strategies like reappraisal involve the prefrontal cortex reinterpreting a situation to change its emotional impact, showing how thought can reshape the way we feel. 10

The brain's default mode network, active during daydreaming or self-reflection, is also involved in processing complex emotions like shame, guilt, pride, or regret, influencing how we view ourselves. 11

Fear responses begin in the thalamus, which quickly relays sensory information to the amygdala, creating a “fast path” reaction before detailed analysis occurs in the cortex. 12

Empathy activates a combination of brain regions, including the insula, ACC, and mirror neurons, allowing us to feel another’s emotional state and guide socially sensitive behavior. 13

Emotional dysregulation in conditions like borderline personality disorder or PTSD often involves impaired communication between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex, resulting in overwhelming feelings.

Humor engages multiple brain regions, including the temporal lobe and prefrontal cortex, combining cognition and emotion to generate laughter—a powerful emotional and social bonding tool. 14

Anger processing involves both the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex. The latter helps control aggressive impulses and decide when it’s appropriate to express or suppress anger. 15

Social rejection activates the same brain regions as physical pain, especially the anterior cingulate cortex, highlighting how deeply emotions like loneliness and exclusion affect our brains. 16

Philosopher Baruch Spinoza believed emotions were tied to the body's drive for self-preservation. His view echoes modern neuroscience, where emotions are seen as tools to guide survival-enhancing behavior. 17