“

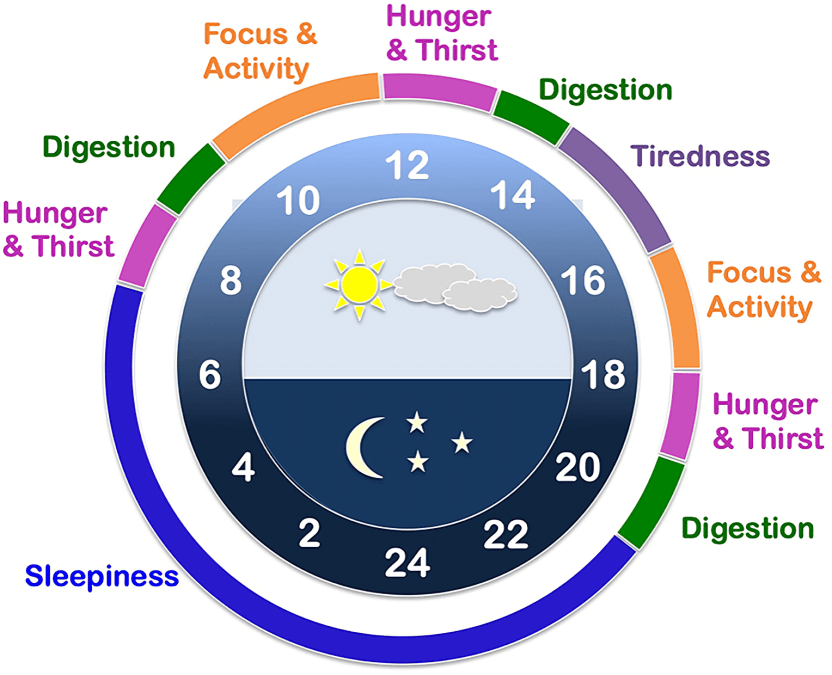

The circadian rhythms and sleep-wake cycles are natural internal processes that repeat roughly every 24 hours, controlling when we feel sleepy or alert. These cycles are deeply connected to brain function, body temperature, and hormone levels, aligning our bodies with the external environment—particularly the rising and setting of the sun. 1

1

”

The brain’s suprachiasmatic nucleus uses light from the eyes to track time, signaling hormones, and adjusting biological processes so the body knows when to sleep or stay alert. 1

Melatonin, a hormone from the pineal gland, increases after sunset, gradually preparing the body for rest by slowing down brain activity and promoting the onset of deep, uninterrupted sleep. 2

Human biological clocks are slightly longer than 24 hours, but external light cues—especially daylight—reset them daily, keeping internal processes aligned with consistent day-night patterns.

Bright morning light signals the brain to stop melatonin production and boost alertness, helping reset the body’s internal rhythm and establish better consistency in daily energy and rest cycles. 3

Screen time before bed can cause delayed hormone release, as blue light tricks the brain into thinking it’s still daytime, making falling asleep harder and disrupting night-time body functions. 4

Jet lag shows how shifting time zones can confuse the body’s timing, leading to fatigue, digestive issues, poor concentration, and temporary changes in mood and immune responses. 5

Night-shift workers often sleep during daylight and stay awake at night, which conflicts with natural body timing and increases long-term risks of heart disease, diabetes, and emotional stress. 6

Cortisol, which boosts morning alertness and focus, peaks early in the day and tapers off toward night, helping the body unwind and slowly transition into a restful state. 7

Core body temperature dips before bedtime and rises just before waking, guiding the brain and muscles to either power down for rest or re-energize for the coming day. 8

Teenagers experience a natural shift in sleep timing due to delayed hormone release, often preferring later bedtimes and struggling with early morning routines, especially during school days.

Going to bed and waking at different times each day disturbs internal stability, leading to mental fatigue, hormonal imbalance, and poor recovery even when total sleep time seems enough. 9

Without light input from the eyes, people who are blind may develop irregular rest patterns and need medical help to regulate timing since their body lacks natural light guidance. 10

Waking from deep sleep phases at the wrong timing causes grogginess, known as sleep inertia. It’s strongest when the body is misaligned with its natural rhythm of rest cycles. 11

Scientists describe two main drivers of rest: sleep pressure and internal timing. Together, they help the body know when to fall asleep and how deeply to rest throughout the night. 12

Social jet lag occurs when people sleep late on weekends but rise early on weekdays. This irregularity mimics the effects of real jet lag and affects alertness and metabolic health. 13

Older adults tend to feel sleepy earlier and wake sooner due to reduced melatonin release and natural timing shifts that occur with age, often changing preferred schedules significantly.

Physical activity at different times of day can shift internal patterns. Morning workouts reinforce early wakefulness, while evening sessions may delay rest readiness in sensitive individuals. 14

Spending long nights online or gaming can keep the brain stimulated and delay readiness for sleep, throwing off natural regulation and reducing both quality and duration of rest. 15

Babies need months to form consistent rest cycles. Early rhythms follow feeding and light exposure, slowly adjusting as the brain matures and adapts to regular day-night transitions. 16

In the 1930s, Nathaniel Kleitman discovered the body’s biological clock continued cycling even in darkness, proving internal mechanisms—not external light alone—govern human rest patterns. 17