“

Appetite and thirst regulation are a vital part of how the brain maintains balance in the body. Controlled mainly by the hypothalamus, this system ensures we eat when energy is low and drink when hydration is needed. It uses hormones, nerve signals, and even emotional responses to keep internal conditions stable.1

1

”

Greek physician Galen was among the first to describe how the brain influences appetite and thirst, proposing that bodily humors and brain structures together shaped the body’s internal needs and external cravings. 1

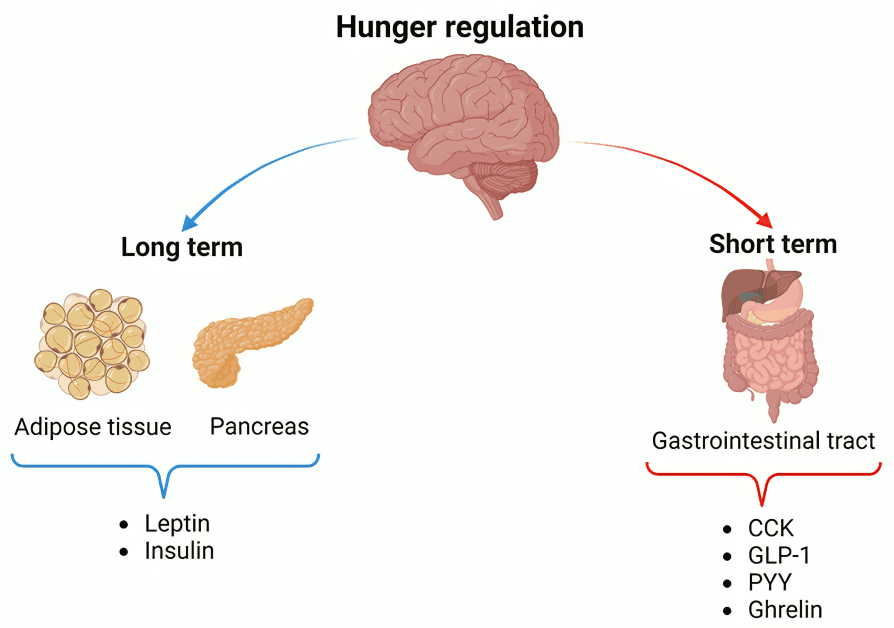

The hypothalamus is the brain's master regulator for appetite and thirst regulation, integrating hormonal signals like ghrelin for hunger and vasopressin for hydration to guide essential survival behavior.2

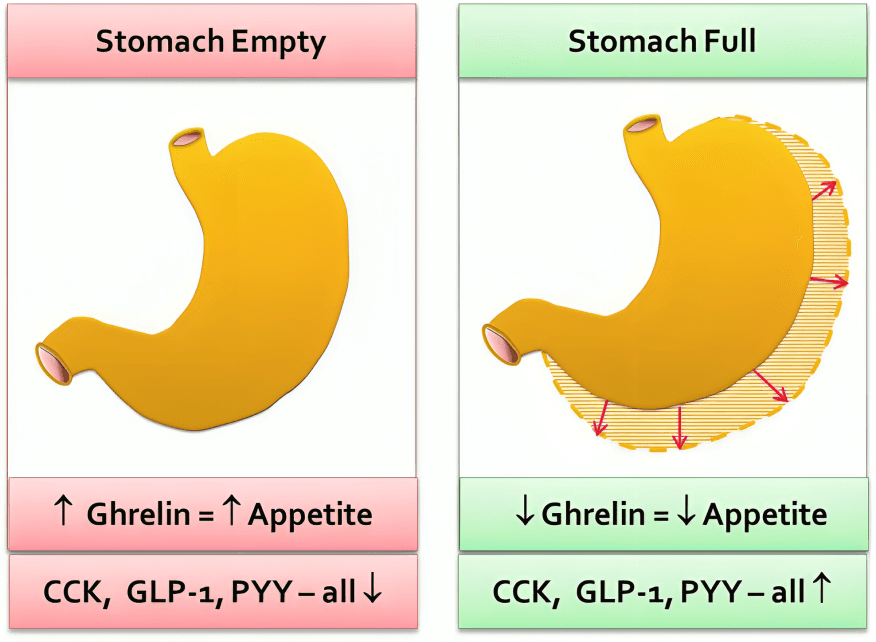

Ghrelin, often called the "hunger hormone," is released from the stomach when it's empty. It travels to the brain to stimulate appetite and prepare the body for food intake.

Leptin, secreted by fat cells, reduces hunger by signaling to the hypothalamus that the body has enough energy stored. It plays a major role in long-term appetite and weight regulation. 3

Thirst is triggered when specialized osmoreceptors in the hypothalamus detect low water levels in the blood, activating a powerful urge to drink and helping restore fluid balance. 4

The hormone vasopressin, or antidiuretic hormone (ADH), conserves water in the kidneys and is released when the brain detects dehydration, working closely with thirst to maintain body water levels.5

Appetite is not only influenced by hunger signals but also by environmental cues, such as the sight and smell of food, which activate brain reward circuits and enhance the desire to eat.6

After eating, the stomach stretches and sends signals via the vagus nerve to the brain, informing it of fullness. This physical feedback helps stop overeating and supports appetite and thirst regulation.7

Drinking fluids too rapidly when extremely thirsty can be regulated by the body’s anticipatory mechanism, which quickly turns off thirst before full hydration is reached to avoid water overload.8

The arcuate nucleus in the hypothalamus contains two major types of neurons: one set promotes hunger (NPY/AgRP), while another suppresses it (POMC/CART), working in opposition for balance.9

Dehydration can significantly impair appetite and thirst regulation. Without adequate fluids, people may experience false hunger cues, fatigue, or confusion as the brain struggles to restore balance.

Certain medications, like antidepressants and antipsychotics, can disrupt normal appetite and thirst regulation by altering brain neurotransmitters, sometimes leading to weight gain or excessive fluid intake.10

Appetite increases in cold environments because the body seeks more energy to stay warm, while thirst often decreases despite fluid loss through respiration and skin evaporation, complicating regulation.11

Emotional stress affects appetite and thirst regulation by influencing cortisol and adrenaline levels. Some individuals eat more under stress, while others may lose interest in both food and water.12

Sleep deprivation disrupts appetite and thirst regulation by lowering leptin and raising ghrelin levels, which increases hunger, reduces satiety, and can lead to overeating or dehydration. 13

High salt intake stimulates thirst by increasing sodium levels in the blood, prompting the hypothalamus to initiate a thirst response, and causing the kidneys to conserve water through ADH release.14

People with damage to the hypothalamus may experience severe dysregulation, including excessive eating (hyperphagia) or lack of thirst (adipsia), highlighting how crucial brain centers are for this control.15

Appetite and thirst regulation also rely on gut hormones like peptide YY and cholecystokinin (CCK), which are released during digestion to signal fullness and help stop both food and fluid intake.

In individuals with diabetes, both hunger and thirst may increase due to high blood glucose levels, as the body tries to dilute the sugar concentration by promoting more drinking and food intake.16

During fasting, the body conserves energy by lowering metabolic rate, reducing hunger signals, and increasing fat usage, showing how appetite and thirst regulation adapt to maintain balance.17